Josef Hofer

I heard about Josef Hofer from my friends in Europe and the United States where he was already a well-known artist. It made me wonder why he was not known here in Brazil. This was when I remembered a fundamental thesis of mine: art is regional. It explains why an artist can be known in the northern hemisphere and not in the southern hemisphere. This happens all the time.

The story and work of artist Josef Hofer fits into the movement known as Art Brut, a term coined by Jean Dubuffet, a French painter who in the 1950s wrote a manifesto about it. It shed light on the much discussed and controversial subject.

A native of Austria, deaf, dumb and mentally handicapped, Josef Hofer lived in psychiatric residences in Austria that catered to people with problems similar to his. As an adult, he was fortunate to be in the right place and time when Dr. Elisabeth Telsinik worked at one of these institutions. This is where the story of Josef Hofer's talent recognition and ascent to becoming great artist begins.

His first solo exhibition was at the Lausanne's Musée d´Art Brut in Switzerland. It was created thanks to Jean Dubuffet, who donated his entire Art Brut collection to the institution. This was followed by many other exhibitions in institutions and commercial galleries in various countries.

Dr. Telsinik lives in Salzburg, a charming little town in Austria where an annual summer music festival takes place. I have had the good fortune to attend frequently. Last year I wrote to her and scheduled time to meet. Since Dr. Telsinik is the appointed curator for Josef Hofer, she takes care of him and his entire collection. I was fascinated with his work and could not resist. Brazilians and the southern hemisphere will now have an opportunity to know this exceptional artist.

Be surprised!

Vilma Eid

Josef Hofer September 9th - 7pm - Opening | 3o floor Exhibition runs through October 9th Galeria Estação

Josef Hofer

Elisabeth Telsnig

(Translation: Betty Tichy Trobisch)

“Art isn’t a pretty accessory – it’s the umbilical cord that connects us with the divine. It insures our humanity.”1

Life did not bequeath Josef Hofer with the best start or the best prerequisites. But he was defiant from the beginning, and brave. He was and is a curious and inquisitive person who looks forward with much anticipation to what life may still bring. He overcomes and masters his congenital shortcomings through his drawings. His art is communicative in its own way, very intimate, very eccentric and unique.

The first significant single exhibition of works by Josef Hofer was given in 2003 in the auspicious Collection de l´Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland. This was followed by others in Austria, Germany, France, Monaco, Netherlands, Belgium, England, Sweden, Denmark, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, USA, Japan and now, in Brazil. His works are represented worldwide within important Art Brut collections and museums. Today, he is considered an Art Brut “classic”.

Josef Hofer was born during the last months of World War II on March 17, 1945, in Wegscheid, Bavaria. His mother (1909-1999), who was 36 and a “late child bearer” at that time, wanted to travel to hospital in the Upper Austrian city of Linz for the birth. However, this was not possible due to the heavy bombing attacks. Instead, she drove across the German border to the nearest hospital. During the “Third Reich”, and indeed, until August (!) of 1945,2 the Law Promoting Genetic Health was in force that required doctors and midwives to immediately report the birth of an impaired child. The consequences were the killing of the newborn and the sterilisation of at least the mother. Little Josef was very fortunate because although his special needs were apparent from the start – he was physically as well as intellectually impaired – nothing was reported to the health authorities.

The parents already had a son who was five year older. The father (1905-1977) was a wood turner and pipe maker. Because both sons were intellectually handicapped, the father gave up his trade and bought a small farm in St. Johann/Wimberg in the Upper Austrian region called Muehlviertel, in hopes that the sons could one day operate the farm and, in this way, earn their living. The parents realised the deadly peril that lurked in the “Third Reich” for those with the label of “life unworthy of life”.3 The father´s oldest sister, Luise Hofer (1879-1941), moved to Wiesbaden as a domestic servant when she was a young woman, developed schizophrenia and from 1925 on, lived in several psychiatric institutions. She was a victim of “Euthanasia”4 in the gas chambers in Hadamar in 1941.

After 1945, Austria was divided up between the four occupation allied forces, USA, England, France and Russia. The area in which the family of Josef Hofer lived remained occupied by Russian troops from 1945 to 1955. As a result of these experiences as a family and the political situation, the parents isolated their younger son; he stayed at the farm and never attended school.

The household lacked hygiene; there was no electricity or any running water. Josef was frequently sick; he had bad teeth and serious inner ear infections that led to the almost complete loss of his hearing. Since he never learned how to use language as a communication tool, he used guttural sounds to express himself and most of all, a wide array of gestures. His extraordinary drawing talent became apparent very early on, even during his childhood. His older brother brought pencils and the stumps of coloured pencils home from school. A sheet of newspaper was often used as a surface.

With his father´s death, his mother was overwhelmed with providing for both sons, so she moved with them to Kirchschlag near Linz where she received some support from her niece, Renate Sager. This niece had three children of her own who became Josef´s playmates. Renate Sager took on the guardianship for Josef and his brother over a period of many years.

Beginning in 1985, Josef was taken to the Lebenshilfe in Grein and Linz during the day, and in 1992, to the Lebenshilfe in Ried im Innkreis, which is where he lives now. The Lebenshilfe is a social organisation for people with physical and intellectual handicaps. I met Josef Hofer in 1997 at the Lebenshilfe atelier that I supervised in Ried until 2015. About 30 individuals took part in my atelier, including Josef, and I noticed his drawings immediately. They were different than anything I had ever seen before. Very soon, I began to collect his first modest drawings on reams of computer paper, and organise them within an inventory and most of all, to carve out the appropriate free space for Josef Hofer himself and his artistic efforts. I worked very hard to ensure that he could develop his gifts on his own. He should be able to work with as much self-determination as possible. In his early sheets, he often depicted objects reflecting the farming life, like tractors, agricultural devices or construction machines. Often he drew objects that were part of his domestic surroundings, like furniture or his clothing. Special events were recorded in his drawings like outings, Christmas Eve festivities or his hippotherapy sessions. Whenever he drew figures, he penciled them in first naked and then added the clothing layer by layer over them, often even covering the face as if with a protective helmet, so that the figures finally ended up looking like they were inside a suit of armour. On the other hand, he would scribble very revealing erotic scenes, eruption-like, onto a piece of paper with naked bodies that were contorted or often entangled in each other. This ambivalence points to his autism on the one hand into which he retreated on the grounds of his hearing loss, and on the other hand, his fantasies and desires which he was able to express through the medium of drawing.

A crucial event took place for Josef in 2000 with the purchase of a mirror, measuring a meter square, which he placed on the floor of his room and with which he could now observe himself for hours on end. In the mirrored vision, he recognised his “alter ego”, which he then reproduced in numerous erotic drawings. It is quite fitting to refer to this as the “mirror phase”, a term used by the French psychoanalytic, Jacques Lacan. Lacan describes here the developmental phase of a child at the point when the child first completely sees that image and encounters and experiences him or herself as “I”. Josef Hofer´s intellectual and emotional development certainly lagged behind considerably. In the act of obtaining and owning the mirror, combined with the encounter with his own body, Josef Hofer experienced the discovery of his own self, his manhood, and he recreated this discovery as a result in his drawings. Hofer´s self-portraits mark the emergence of his self-awareness.

If at first the objects and persons were lined up on the surface of the drawing in an isolated manner, beginning in 2003, Josef Hofer began suddenly to surround his drawings with a yellow-orange frame, causing one to think that he wished to protect them in this way. The frame became an obsession that involved him for many hours, first a pencil with the aid of a thin wooden flooring strip, then filling in the geometric pattern with always the same shades of colour – different shades of yellow and orange. In this way, authentic architectural forms were created, full of depth, perspective, a spatial sense. As I watched, I could recognise just how exactly and consciously he would always plan each working stage. Josef had worked for years in the weaving workshop of the Lebenshilfe and this to-and-fro of the weaving process seems to have been etched as an image into his memory. These magnificent yellow-orange framework constructions reflect the autism of Josef Hofer, the protective bars of his soul into which he lets us viewers peer to see a small portion, as if through a window.

From 2014 onwards, the frames became increasingly finer and Hofer filled in the background frequently since then with the letters in his nickname “PEPI”.

Josef Hofer has always worked within a series. If he is fascinated by a motive, then he repeats it again and again, almost obsessively, sometimes with only minimal variations. Whenever one observed him at his work, as unobtrusively as possible, one had the impression that he would try to capture the motive, on a search for the optimal design, the perfect image. Only then was he able to move on to a new motive.

The ability to express himself and communicate about his drawings has great significance to Josef Hofer. Since he cannot hear or make himself understood verbally, he communicates with the outside world through his art. This he does successfully with great expressiveness, competence and a captivating ease. He is creatively involved with himself and his body, and just as in the way he is involved with his mirror reflection, he becomes involved equally with the postures and positions of the depicted body, and overcomes, or even triumphs over his own disability through the bodies he draws.

Perhaps it is in this involvement with the depicted bodies and positions, and with the forms and obsessive repetitions even to an excessive degree, that a certain proof can be found for Hofer´s affinity for the work of Egon Schiele (1890-1918). The book by Jane Kallir entitled Egon Schiele. Drawings and Watercolours, was given to Hofer in 2007, and he poured over it for countless hours, fully mesmerised. He took a few select motives from it and interpreted them again and again in his own way. It can be said that he found himself to a point in the art of Egon Schiele. He describes the characteristic forms and gestures of Schiele but remains true to himself in terms of style.

In Austrian literature, Arthur Schnitzler (1862-1931) was the first to deliberately implement the so-called “inner monologue” in his novel Fräulein Else (1924). “Inner monologue” means that a literary figure addresses him or herself directly. We discover this “inner monologue” in the art of painting with Egon Schiele´s self-portraits. In Art Brut, Josef Hofer continues to conduct this dialogue with himself. In his self-portraits, Josef Hofer also includes the viewer into his picture as well. It seems as if the viewer stands in front of the mirror instead of Hofer and looks at the picture – the self-portrait of Hofer.

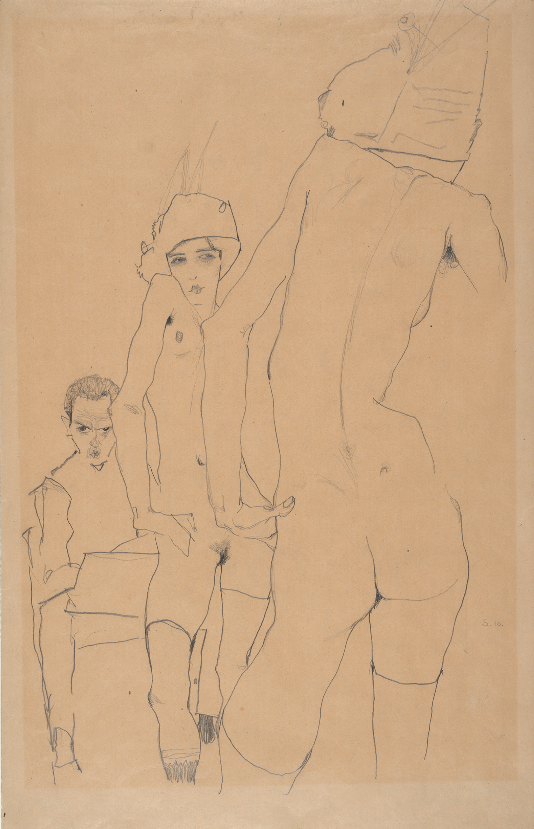

A pencil drawing by Egon Schiele from 1910 entitled Schiele with Nude Model before the Mirro5 (s. fig. 1) shows the back of a female nude with a hat in the foreground; on the left side, in an imaginary mirror, the nude is seen from the front, and behind, left – also in the imaginary mirror – is the self-portrait of the seated artist. Front view and simultaneous back view of a figure in a single drawing are to be found with Josef Hofer as well. The creative act, however, is completely different. In this drawing Schiele utilises the imaginary mirror as a tool and tries to reproduce a real situation. Hofer dispenses with such tools, ignores the so-called reality and draws the front and back views in just one figure. Josef Hofer defies logic of any kind. He does not even attempt to depict the real outer appearance. What he offers instead in his depictions is how he physically senses and experiences the figures and objects. Due to his deafness, Hofer commands another experiential mode through spatial orientation. The bodies he depicts exhibit such dynamics of movement that they can often seem manneristic. The front and back views merge into each other, like a face into the back view of the head or the body of a man into that of a woman. He merges both into one, into androgynous figures. Whether the bodies, objects or letters are reversed, back to front, is of no importance to him. Whether heterosexuality or homosexuality is of no concern to him, since he does this innocently and absolutely free of intentionality. In this way, he breaks with all the western, occidental traditions. The depiction of his figures is utterly different than anything done before – it is ingenious, and, yes, revolutionary. Josef Hofer developed his own system for appropriating art and he set new benchmarks for figurative representation. He has achieved a sensual, symbolic implementation of figurative drawing.

Today, Josef Hofer is more than 74 years old and only draws now and then.

Notes

1 Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1929-2016), Austrian conductor, cellist, author on music and pioneer in the field of historical performance practice.

2 The World War II was over on May 8, 1945, following the unconditional capitulation of the German armed forces.

3 The Nazi regime labelled a person “life unworthy of life” for humans with cognitive and physical defects, with genetic diseases, homosexuals among others. Binding/Hoche coined the term in their brochure "Allowing the destruction of life unworthy of life, its measure and its form” (Leipzig, 1920).

4 “Euthanasia”, destruction of “life unworthy of life” and the Nazi-murders of psychiatric patients, also known as “Action T4”. “Action T4” is named after the central office of the Chancellery department set up by the Führer in Berlin at Tiergartenstrasse 4. It stood for the organisation of “Euthanasia” crimes from 1939 to August 1941. The description “T4” is not a camouflaged term coined by the National Socialists but an idiom used during the post-war years.

5 Egon Schiele (1890-1918), Schiele with Nude Model before the Mirror, 1910, pencil on wrapping paper, Albertina, Vienna, Inv. Nr. 26276.

fig1

Egon Schiele (1890-1918), Schiele with Nude Model before the Mirror, 1910, pencil on wrapping paper, Albertina, Vienna, Inv. Nr. 26276.

Galeria Estação

Presents

Solo exhibitions by Fernando Diniz and Josef Hofer, artists whose differences of mind and body find no limits in art

Opening:September 9 at 7 pm

Until October 9, 2019

The two exhibitions unfold the International Seminar that takes place in parallel to “Creation of Worlds - Bishop of the Rosary”, the show at the Marcos Amaro Foundation, in Itu, on September 7th. The event is supported by the Galeria Estação that brings Dr Elisabeth Telsnig as one of the speakers. She is the tutor of Josef Hofer's work and curator of his exhibition.

Fernando Diniz (1918, Aratu, Bahia - 1999, Rio de Janeiro, RJ) is among the forged artists in the environment of Dr. Nise Da Silveira, gathered at the Museum of the Unconscious Images, partner institution of Galeria Estação in the realization of this individual in his tribute. Curated by Luiz Carlos Mello and Eurípedes Junior, the institutional show brings a cut of paintings from Diniz's production estimated at about 30,000 pieces, including canvas, drawings, rugs and modeling. With his work listed by the Institute of National Historical and Artistic Heritage in 2003, the artist's recognition is also hailed by the numerous exhibitions in Brazil and abroad, as well as awards, publications, films and videos.

“It's not me, it's the paints,” was his answer when he attended, from 1949, the Occupational Therapy Section of the Pedro II Psychiatric Center, created by Dr. Nise. According to the curators, Diniz mixes the figurative and the abstract, ranging from the simplest to the most complex structures of composition. "Constant presence is geometrism, often marked by the image of the circle, which represents the ordering, healing forces of the psyche."

In addition to producing intensely - from four to six pieces a day - Fernando Diniz collected all the papers he found in the hospital and its surroundings, taking them to his room. There, he used these materials as a support for his creations, calling them “Recycled”. Old sheets thrown away by the hospital administration were recovered by him: he sewed them up and built supports for the large paintings he called Digital Rugs.

The curators highlight the artist's eagerness for knowledge, who came to imagine the hospital as a university. “His passion for books made him constantly up to date with scientific events and discoveries. He was interested in astronomy, chemistry, nuclear physics and computing, proving to be a tireless researcher. ” His curiosity for knowledge led him to the cinema. It was his participation in Leon Hirszman's In Search of Everyday Space that sparked his interest in the movement of the image. This interest resulted in the award-winning eight-pointed star cartoon, for which he created more than 40,000 drawings under the guidance of filmmaker Marcos Magalhães.

In 1992 the Museum of the Unconscious Images held a major retrospective of his work, The Universe of Fernando Diniz, that occupied, with more than two hundred works the spaces of the Imperial Palace of Praça XV, in Rio de Janeiro.

“From space to time, from inorganic to organic, from geometric to figurative or vice versa, Fernando was weaving his universe. He visited the interior spaces of the dreamed house, and the expanse of landscapes; he fragmented or rebuilt the human body, subjecting it to the movements of games, sports; he schematized objects and beings, imagined scientific objects, executed true geometric tornadoes with shapes whose extreme multiplicity sometimes led him to chaos, from where he always returned by bringing new and unexpected images, such as his latest abstracts, where logos, chemical formulas, signs and symbols blend to create a lush universe of things, an inventory of the world”, conclude Luiz Carlos Mello and Eurípedes Junior.

Josef Hofer (1945 in Wegscheid, Bavaria), today considered a “classic” by Art Brut, has his work known in Austria, Germany, France, Monaco, the Netherlands, Belgium, England, Sweden, Denmark, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, the United States, Japan and now in Brazil. It is hard to imagine how an artist has reached his 74th birthday today in the face of so many difficulties. It began with his birth in March 1945, when, until August of the same year, the German People's Genetic Health Protection Act was in force in Germany. That required doctors and midwives to report immediately the birth of a disabled child. The consequences were the death of the newborn and at the sterilization of the mother to say the least. Although their differing physical characteristics were visible from the outset, nothing was reported to the health authorities. Later, isolated with his family on a farm, also with hearing problems caused by countless ear infections that also affected his speech, he could not attend school, as his older brother. But even with intellectual disabilities, he brought home pencils and crayons that Hofer used to draw on a sheet of newspaper. Upon his father's death, Hofer was taken by his mother to Kirchschlag, near Linz, where he was kept by a niece. He’s been living in Lebenshilfe in Ried im Innkreis. Lebenshilfe since 1992, a social organization for people with physical and intellectual disabilities. That is where in 1977 he met the art historian Elisabeth Telsnig. “About thirty people attended my studio, including Josef, and I immediately noticed his drawings. They were unlike anything I'd ever seen, ”says Telsnig.“Unable to hear or to be understood verbally, Josef Hofer communicates with the outside world through his art. He is creatively involved with himself and his body, just as he is involved with his reflection in the mirror, he engages equally with the postures and positions of the represented body, and overcomes, or even triumphs over his deficiency through the bodies. that he draws, ” she adds.

Elisabeth Telsnig is a curator, Ph.D. in art history and head of the creative activities workshop at the Lebenshilfe Oberösterreich community facility in Ried (Austria), where Josef Hofer participates weekly. She has been his tutor since 1997.

About the International Seminar: Art as a Construction of Worlds ".

Location: Marcos Amaro Foundation / Itu / September 07

The meeting – organized by ARTE!Brasileiros - aims to present to the public the enormous richness and diversity of artists, former psychiatric patients in Brazil and worldwide, linked to the movement initially named by French painter Jean Dubufett as Art Brut, and to debate the beauty and strength contained in the production of works by asylum artists.

Elisabeth Telsnig (representative of the work of the Austrian artist Josef Hofer), Savine Faupin (Chief Curator responsible for Brute Art at the Museum of Modern, Contemporary and Art Brute in Lille, France), Tânia Rivera (psychoanalyst, PhD in Psychology) and professor at the Fluminense Federal University) and Raquel Fernandes4 (general director of the Bishop of the Rosary Museum of Contemporary Art, Rio de Janeiro). The conversation will be mediated by Ricardo Resende (curator of the Marcos Amaro Foundation and the Bispo do Rosário Contemporary Art Museum).

Information: jamyle@artebrasileiros.com.br - eliane@artebrasileiros.com.br

Exhibitions: Fernando Diniz and Josef Hofer

Opening: September 09 at 19h

Visitation until October 09, 2019

Free classification

From Monday to Friday, from 11am to 7pm, Saturdays from 11am to 3pm - free admission.

Pictures: https://bit.ly/2GZSzFn

Galeria Estação

Rua Ferreira de Araújo, 625 - Pinheiros - São Paulo

Phone: 55 11.3813-7253

www.galeriaestacao.com.br

Press Information

Pool de Comunicação - Marcy Junqueira / Martim Pelisson / Ana Junqueira

Phone: 11.3032-1599

marcy@pooldecomunicacao.com.br / martim@pooldecomunicacao.com.br / ana@pooldecomunicacao.com.br